The consistent globally top-ranked government think-tank, Philippine Institute for Development Studies, in its review of transport infrastructure said we do not just tail our Asian neighbors in quantity and quality of road and rail transport infrastructure.

In fact, the 2019 Global Competitiveness Index rates us poorly in road connectivity and quality, railroad density and efficiency of train services. While noting some improvement in the quality of national roads, the PIDS noted that more local roads are rated “poor” to “bad” than “good” to “fair.” Many bridges remain temporary (i.e., made of timber and bailey) and need replacement with more permanent concrete and steel. They also noted how our active railways shrank drastically from over a thousand kilometers in the 1970s to only 77 km in 2016. This had increased again to 395 km by 2021, but load factor data reveal severe congestion in rail transit systems in Metro Manila. Harassed daily city rail commuters need not see the data to know that our rail transport system is woefully behind.

With PIDS pointing out such defects and slow implementation of projects, it is tantamount for government to listen and act to improve not just our image but to deliver the services due to the taxpayers, particularly the middle to lower incomes whose contributions cannot be ignored.

The researchers also observed severe capacity and technical limitations also in the air transport sector. Even back in 2016, NAIA already exceeded its handling capacity (of 35 million) by 5 million passengers. Only 22 of the 90 national airports are equipped for night use.

Oxford Economics scored us lowest on aviation infrastructure in the region and this calls for an overhaul of the institutional environment for air transport, citing past recommendations for an integrated system and improved interagency coherence, convergence, and coordination, wrote former NEDA Secretary Cielito Habito in his column.

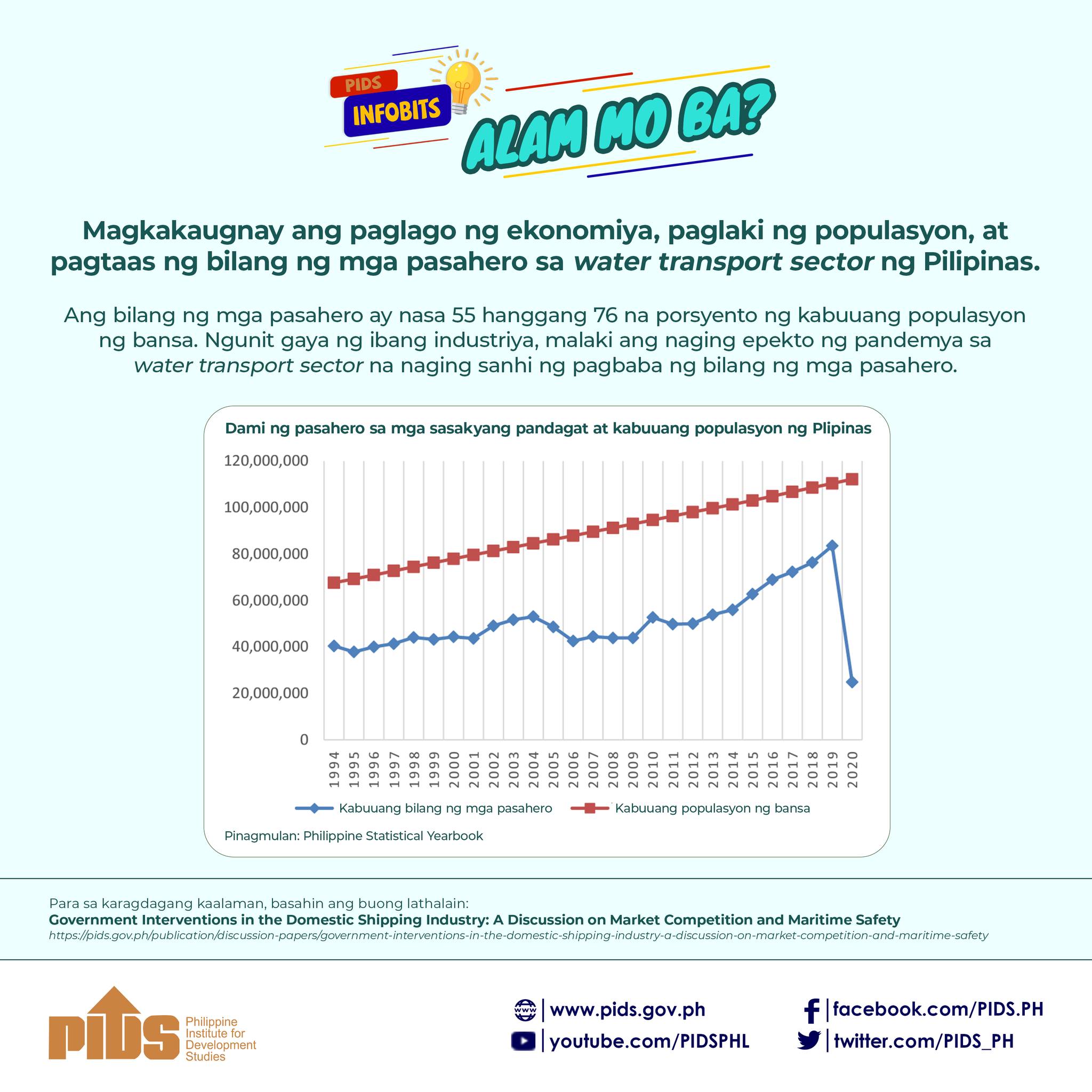

Recent maritime accidents highlight the same woes in the water transport sector. There may be enough seaports in the country but most are underdeveloped and underequipped, with most major ports suffering from congestion. The result is imbalanced port utilization, with ports having uneven capacity and capability.

Institutional issues also hound the water transport sector because of conflicting roles of government agencies and a lack of coordination in port planning, the PIDS said pointing out the Philippine Ports Authority’s conflicting roles as developer, operator, and regulator of ports, and yet this basic anomaly remains unaddressed.

These institutional issues have contributed to the low quality of services and inefficient functioning of public ports. The PIDS cites the main challenge as “the absence of institutional anchoring for overall integrated planning for multimodal transport.”

Despite being a declared goal in the 1990s, the seamless multimodal transport stands to connect the rails to the airport terminals and to the ports.

Vested interests in the taxi industry had prevailed over public interest and prevented such connections from happening.

If infrastructure planning is not based on the greatest good for the greatest number, little will be gained in closing the infrastructure gap with our neighbors, as we’ve failed to do for decades now.

And we haven’t even touched on power, water, and telecommunications, where our inadequacies are equally, if not more daunting, Habito concluded.