Enhancing the capacity of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to resist, absorb, and recover from the effects of natural disasters in a timely and efficient manner is key to achieving inclusive growth in the APEC region.

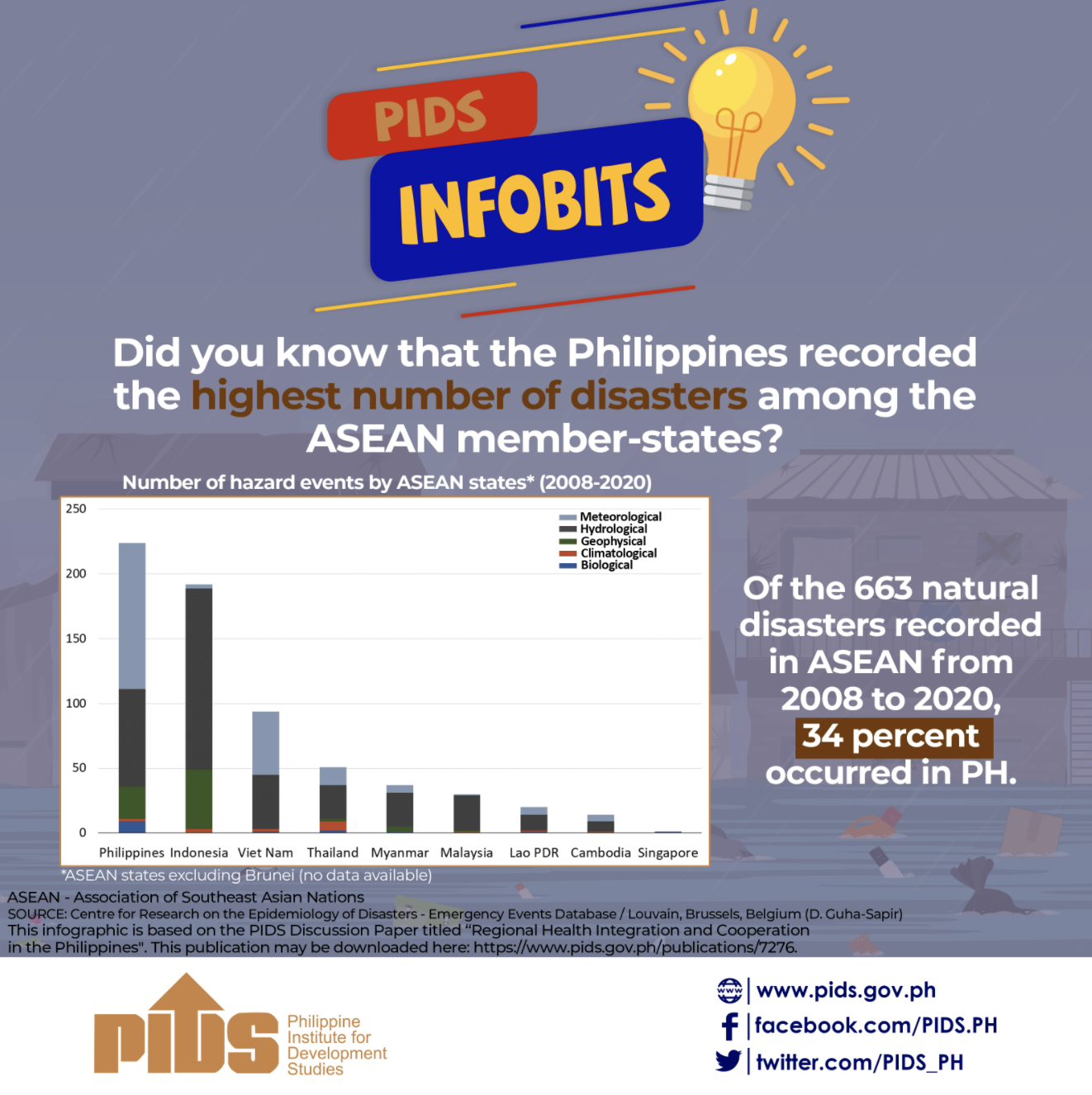

SMEs are considered engines of growth and employment in the APEC region. Over 97 percent of businesses in APEC are SMEs, providing jobs to more than half of the workers in the Asia-Pacific region. However, APEC member-countries are prone to intense natural disasters. APEC`s 21 member-economies, which account for 52 percent of the earth’s surface and 59 percent of the world’s population, experience over 70 percent of global natural disasters.

According to Marife Ballesteros, senior research fellow at state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), disasters can compromise capital, supply chains, product markets, and labor, and in turn, business continuity and recovery.

In her presentation at the 2015 APEC Study Centers Consortium Conference titled `Building Philippine MSMEs` Resilience to Natural Disasters`, Ballesteros noted that `SMES are more vulnerable (than large enterprises) because they have limited coping mechanisms. SMEs usually have no or limited disaster insurance and limited access to credit, and most of them have no business continuity, emergency management, or disaster preparedness plans.`

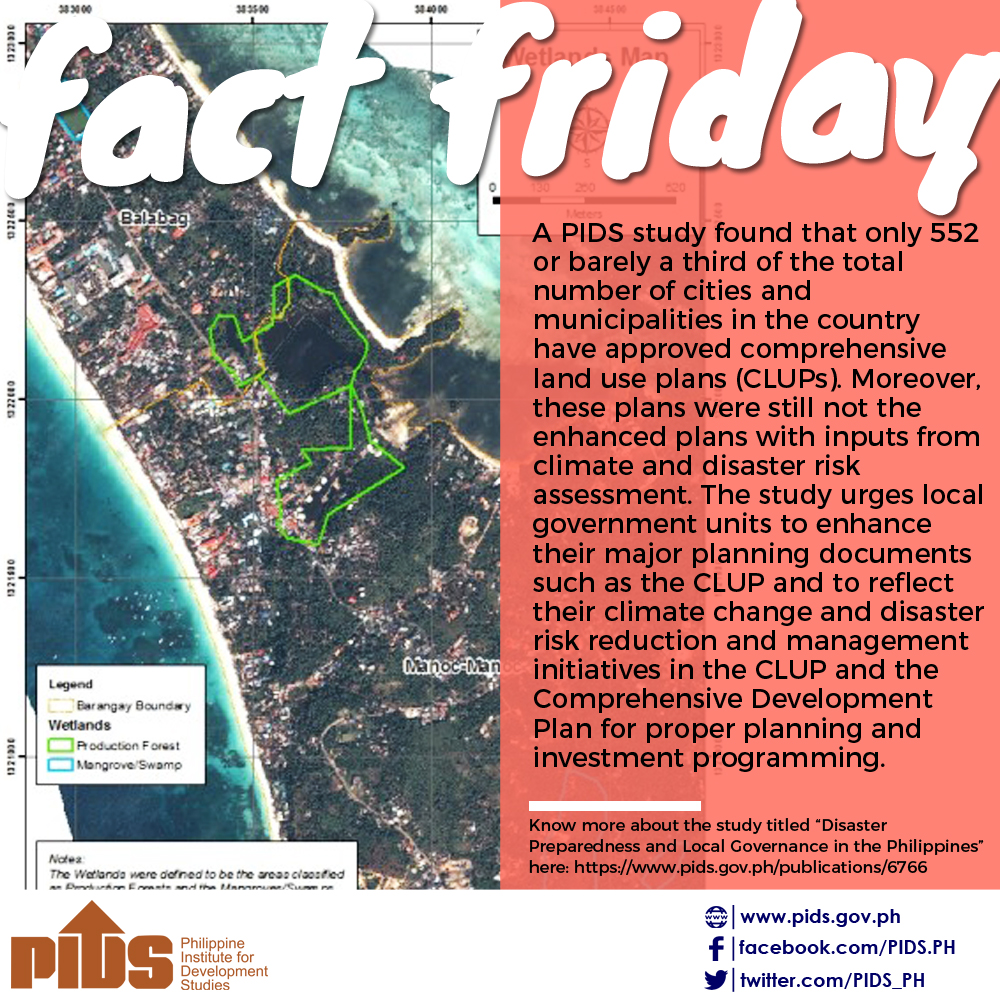

Ballesteros cited the case of the Philippines, where approximately 98 percent of all enterprises are micro to small. She noted that the country has a well-developed policy framework and action plans for DRRM. However, this disaster response strategy has not been effectively translated into local and business plans.

`The DRRM plans of the Philippine government are operationalized primarily for search, rescue, evacuation, and relief operations. Restoration of economic activities is handled only in the medium to long term as part of the rehabilitation efforts. There is also no strategic programs to operationalize action plans for SMEs and no small business development centers to address disruption and needs,` she explained.

In addition, she pointed out the insufficient recovery funds for farm-based and urban-based small industries such as the availability of loan and grant for these businesses.

Another issue highlighted by Ballesteros is the absence of specific policies for workers` protection in times of calamities. She emphasized the importance of the people side of business during disaster. `Resilient supply chain begins with resilient citizens and employees and it is a concern of both business and government,` she stated.

She cited the business continuity plan of Albay Province as a model for implementing DRRM for SMEs. Albay`s model covers both households and local businesses. It encourages local businesses to develop contingency plans based on vulnerability and hazard maps as well as land use zoning. This kind of local initiatives should be scaled up and replicated in other localities.

At the national level, Ballesteros recommended the establishment of key transport hubs and strategic communication systems that take into consideration extreme weather events.

She also highlighted the need for predisaster agreements as disruption of public sector operations and services can occur during times of calamities. One of these is the creation of networks or partnerships between national and local, and public and private entities, and the adoption of flexible regulations on labor as well as laws on importation and exportation.

In addition, government must support the development of financial security instruments such as catastrophic insurance, micro insurance, or a business disaster fund. She also suggested the integration of DRRM in the Magna Carta for SMEs and BMBEs as well as in the MSME Development Plan.

In the APEC region, Ballesteros called for cooperation to strengthen supply chain resilience. She proposed that `SMEs should continue to build partnerships with other multinational organizations inside and outside of the APEC region, especially in the areas of information sharing and promotion of regional resiliency assessment programs. APEC member-economies can also have dialogues, capacity-building activities, and cross collaboration in resource and technology sharing such as in hazard mapping and information technology infrastructure`.

The APEC Study Centers Consortium Conference 2015 was held on May 12-13 in Boracay, Aklan Province, as part of the Second Senior Officials Meeting (SOM2) and Related Meetings of APEC 2015. It was organized by PIDS and the Philippine APEC Study Center Network in collaboration with the Ateneo de Manila University and the Asian Development Bank Institute. The annual conference provides academics and scholars from the different APEC study centers with a venue to discuss and exchange ideas on the APEC themes and to identify areas for research collaboration. The output of the conference discussions may serve as inputs to the different APEC working group discussions and may be integrated in the Leaders` statement.

SMEs are considered engines of growth and employment in the APEC region. Over 97 percent of businesses in APEC are SMEs, providing jobs to more than half of the workers in the Asia-Pacific region. However, APEC member-countries are prone to intense natural disasters. APEC`s 21 member-economies, which account for 52 percent of the earth’s surface and 59 percent of the world’s population, experience over 70 percent of global natural disasters.

According to Marife Ballesteros, senior research fellow at state think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS), disasters can compromise capital, supply chains, product markets, and labor, and in turn, business continuity and recovery.

In her presentation at the 2015 APEC Study Centers Consortium Conference titled `Building Philippine MSMEs` Resilience to Natural Disasters`, Ballesteros noted that `SMES are more vulnerable (than large enterprises) because they have limited coping mechanisms. SMEs usually have no or limited disaster insurance and limited access to credit, and most of them have no business continuity, emergency management, or disaster preparedness plans.`

Ballesteros cited the case of the Philippines, where approximately 98 percent of all enterprises are micro to small. She noted that the country has a well-developed policy framework and action plans for DRRM. However, this disaster response strategy has not been effectively translated into local and business plans.

`The DRRM plans of the Philippine government are operationalized primarily for search, rescue, evacuation, and relief operations. Restoration of economic activities is handled only in the medium to long term as part of the rehabilitation efforts. There is also no strategic programs to operationalize action plans for SMEs and no small business development centers to address disruption and needs,` she explained.

In addition, she pointed out the insufficient recovery funds for farm-based and urban-based small industries such as the availability of loan and grant for these businesses.

Another issue highlighted by Ballesteros is the absence of specific policies for workers` protection in times of calamities. She emphasized the importance of the people side of business during disaster. `Resilient supply chain begins with resilient citizens and employees and it is a concern of both business and government,` she stated.

She cited the business continuity plan of Albay Province as a model for implementing DRRM for SMEs. Albay`s model covers both households and local businesses. It encourages local businesses to develop contingency plans based on vulnerability and hazard maps as well as land use zoning. This kind of local initiatives should be scaled up and replicated in other localities.

At the national level, Ballesteros recommended the establishment of key transport hubs and strategic communication systems that take into consideration extreme weather events.

She also highlighted the need for predisaster agreements as disruption of public sector operations and services can occur during times of calamities. One of these is the creation of networks or partnerships between national and local, and public and private entities, and the adoption of flexible regulations on labor as well as laws on importation and exportation.

In addition, government must support the development of financial security instruments such as catastrophic insurance, micro insurance, or a business disaster fund. She also suggested the integration of DRRM in the Magna Carta for SMEs and BMBEs as well as in the MSME Development Plan.

In the APEC region, Ballesteros called for cooperation to strengthen supply chain resilience. She proposed that `SMEs should continue to build partnerships with other multinational organizations inside and outside of the APEC region, especially in the areas of information sharing and promotion of regional resiliency assessment programs. APEC member-economies can also have dialogues, capacity-building activities, and cross collaboration in resource and technology sharing such as in hazard mapping and information technology infrastructure`.

The APEC Study Centers Consortium Conference 2015 was held on May 12-13 in Boracay, Aklan Province, as part of the Second Senior Officials Meeting (SOM2) and Related Meetings of APEC 2015. It was organized by PIDS and the Philippine APEC Study Center Network in collaboration with the Ateneo de Manila University and the Asian Development Bank Institute. The annual conference provides academics and scholars from the different APEC study centers with a venue to discuss and exchange ideas on the APEC themes and to identify areas for research collaboration. The output of the conference discussions may serve as inputs to the different APEC working group discussions and may be integrated in the Leaders` statement.