"TO effectively combat bullying, we need to work not just inside the schools, but also in the households and communities where our learners come from. This is not just a school matter; it is a national priority that demands a whole-of-government, whole-of-society response."

This was the message Education Secretary Sonny Angara offered as he convened the executive committee of his department to tackle the growing number of bullying cases in schools earlier this month.

The secretary's observation is borne out by a recent Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) study by Alejandro N. Herrin, Jan L.G. Alegado, Judith B. Borja, Nanette L. Mayol, Francisco M. Largo, Isabelita N. Bas and Michael R.M. Abrigo that shows children who suffer physical bullying at home — especially by parents or adults — are more likely to fall behind in school.

Drawing from a seven-year nationwide study that tracked 5,000 Filipino students, the research highlights how physical abuse in the home significantly disrupts education.

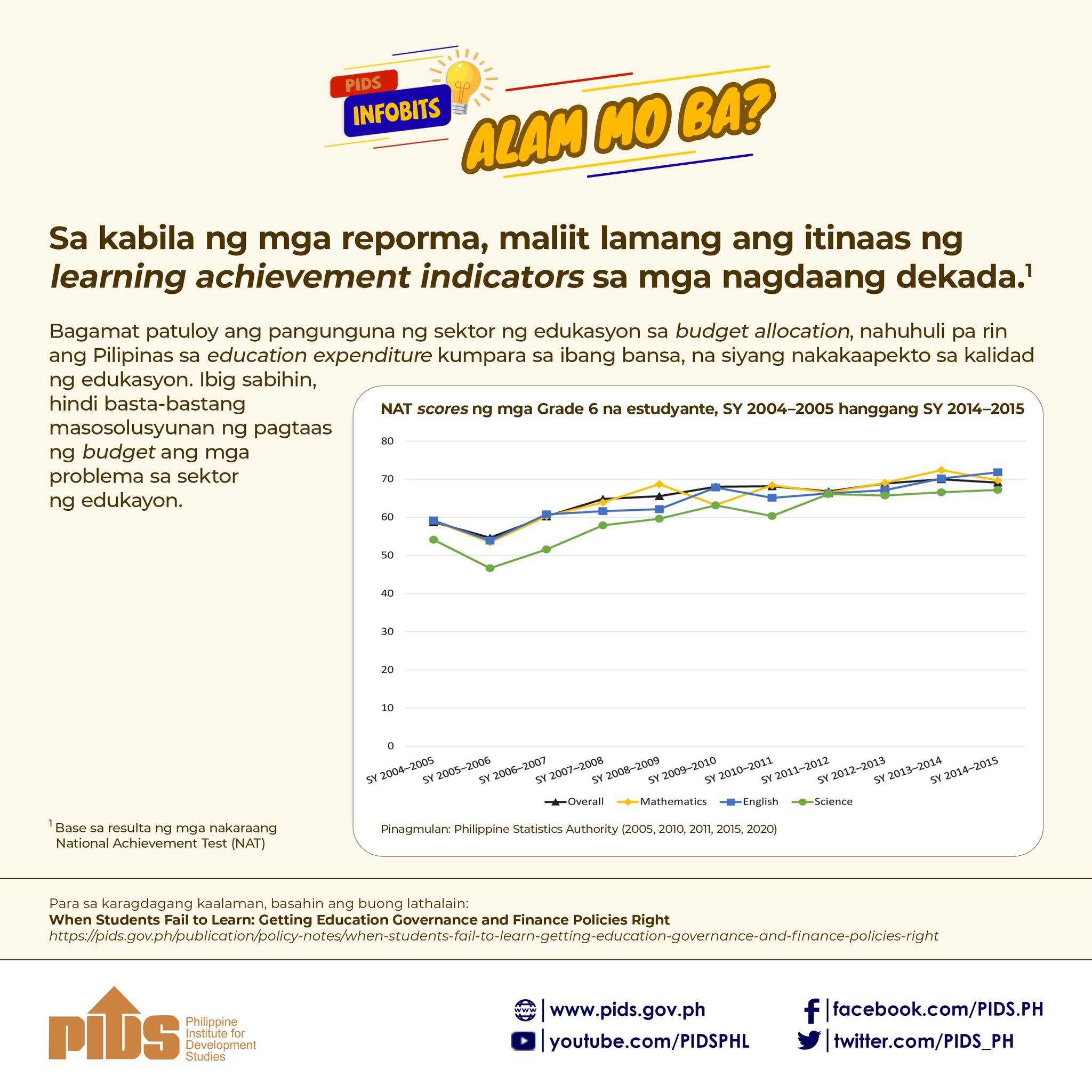

"The 2018 PISA (Program for International Student Assessment) results revealed that the Philippines ranked close to the bottom in reading, mathematics and science but ranked at the top in terms of bullying in school," the authors said. "Analyses of PISA 2018 data found that bullying has a negative effect on school performance."

Presenting the results this month, Herrin, who is a policy adviser at the University of San Carlos' (USC) Office of Population Studies Foundation, stressed the severe impact of adult-inflicted harm.

"It appears that physical bullying, especially from adults and parents, has expected negative effects on schooling outcomes," he said.

Students experiencing physical harm were more likely to miss school and fall behind. Herrin said their data showed that, by the time the students turned 16, 20 percent of them were no longer at the grade level expected for their age.

USC psychology professor Delia Belleza, who analyzed the findings of the PIDS study, said there were three core elements of bullying. First, it must be repeated. Second, it must be intentional; there is really the intention to hurt to embarrass. And third, it involves a power imbalance.

This precise definition helps separate true bullying from normal growing pains, Belleza said.

Moreover, the digital era introduces new challenges to combat bullying.

"We have less control [over] what they click, and they have been involved in a lot of social interactions which [we do not see]," she said, noting how cyberbullying evades traditional monitoring.

As schools in the Philippines implement anti-bullying policies, Herrin identified the core challenge of how policies are implemented.

The PIDS study recommends tailored approaches addressing different types of bullying while leveraging new mental health laws.

Beyond school policies, family and community interventions are crucial. Parents, in particular, play a pivotal role in shaping children's emotional and academic well-being.

Another PIDS study by Abrigo, Edmar E. Lingatong and Charlotte Marjorie L. Relos relates school bullying in the Philippines to learning losses.

"While the magnitude in foregone learning achievement appears to be minimal at around 0.05 standard deviations, their long-term economic implications could be quite substantial at P10 billion to P20 billion per year in lost economic activity," the authors said.

Drawing from the 2018 PISA data, PIDS estimates that 36 percent of Filipino students fall into the top 10 percent of most bullied students globally.

About 76 percent of students reported experiencing at least one form of bullying in the past year. For an estimated 11,000 students nationwide, bullying — ranging from exclusion to threats and extortion — happens almost weekly.

Abrigo, the lead author of the study "School Bullying Contributes to Lower PISA Achievement among Filipino Students: Who Gets Bullied? Why Does It Matter?" highlighted the far-reaching consequences of bullying not just on academic achievements and mental health, but also its negative effects on future employment opportunities and earning potential. As these individual setbacks can accumulate over time and across the student population, they contribute to a measurable loss in national economic productivity.

To quantify the economic implications, Abrigo's team used established human capital models to estimate how learning losses linked to bullying affect future earnings and, consequently, gross domestic product (GDP). They found that bullying accounts for a sizable share of the gap in academic performance. The projected loss to the country's GDP ranges from 0.05 to 0.08 percentage points annually, or about P10 billion to P20 billion.

"This is approximately the budget of the Department of Education (DepEd) for textbooks in 2024, which is about P12 billion, and the whole computerization program of DepEd is about P8 billion," Abrigo said.

All this only underscores the urgency of addressing school bullying — now.