A COUPLE of weeks ago, I attended a forum where Dr. Imelda Angeles-Agdeppa, director of the Food and Nutrition Research Institute, made a presentation on the nutritional status of Filipinos.

I have been writing, for some time now, on nutritional issues and their inextricable link to persistently high food prices in the Philippines compared to other Asean countries. High food prices and inflation have been a scourge for millions of consumers because of flawed agriculture and food policies by successive political administrations.

Our government bats for food self-sufficiency in the face of a rapidly growing population within a limited land area that is fast being converted into commercial and residential areas. It allocates a pittance of the national budget (around 2 to 4 percent) to agriculture despite the sector contributing around 10 percent to gross domestic product (GDP).

It pursues a social justice framework for the development of agriculture, thinking that farmers tilling a hectare of land (due to the protracted implementation of agrarian reform) and who are aging, and have barely completed elementary education, will serve as the backbone in attaining the food self-sufficiency goal.

The result is devastating for ordinary Filipino consumers. Angeles-Agdeppa's presentation revealed that stunting among Filipino kids up to 59 months old was at 29.5 percent, and the incidence of being underweight for the same age group was 19 percent. For children aged 6 months to 5 years, the prevalence of anemia was a whopping 43.1 percent.

Among those 5 to 10 years old, stunting was almost at 25 percent and being underweight at 25.5 percent. Among adolescents ages 11 to 19 years old, stunting was at 26.6 percent and wasting at 11.5 percent. The statistics reveal that at least around a fourth to a third of our kids ages between less than a year and 19 years old suffer from malnutrition (manifested in stunted growth), being underweight and even wasting.

Note that the data set only considers those falling on the threshold and below. Those at the upper border can easily fall below the threshold during economic shocks like parents losing their jobs or getting ill. For most Filipinos, the likelihood of such an economic setback is high given their poor health condition as a result of years of malnutrition. In other words, practically 40 to 50 percent of our kids are threatened by malnutrition.

It is a well-known fact among nutritionists and food scientists that malnutrition affects the brain development of kids, particularly those ages 0 to 5 years old. Almost 90 percent of a person's brain is developed during those critical years. Thus, without proper nourishment during those years, brain development will be permanently damaged.

In the information age, the demand for better cognitive ability and skills, particularly creativity, is more exacting. Rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) means that a lot of clerical, administrative and even manual work will soon be taken over by machines. The problem is that these areas are where people with lower cognitive ability are employed. The AI phenomenon means that these people will eventually find themselves permanently unemployed.

Angeles-Agdeppa's recommendation to address the serious malnutrition problem are to improve the value chain of agricultural and food commodities produced in the country and to lessen food wastage through better postharvest facilities and consumption habits. These have been made by experts in the past with little traction to show. Ostensibly, the attainment of these recommendations will take time — they are long term and at best need five to six years to achieve.

The fastest way to ensure greater access to quality and affordable food, particularly for the poor, is to allow the entry of agricultural and food imports. Import quotas should be removed and tariff rates for agricultural and food items lowered. The private sector should be allowed to import using their money, subject to public health and safety inspections of those food products.

The major opposition to this proposal is the tired and worn-out argument that liberalized agricultural and food trading will hurt local farmers, fishers and small producers. We have, however, been protecting them for over 50 years now, and they remain as dirt-poor as ever. Only a few commercial producers and traders have benefitted immensely from protectionism. This explains why they are the noisiest groups whenever trade liberalization is put on the table.

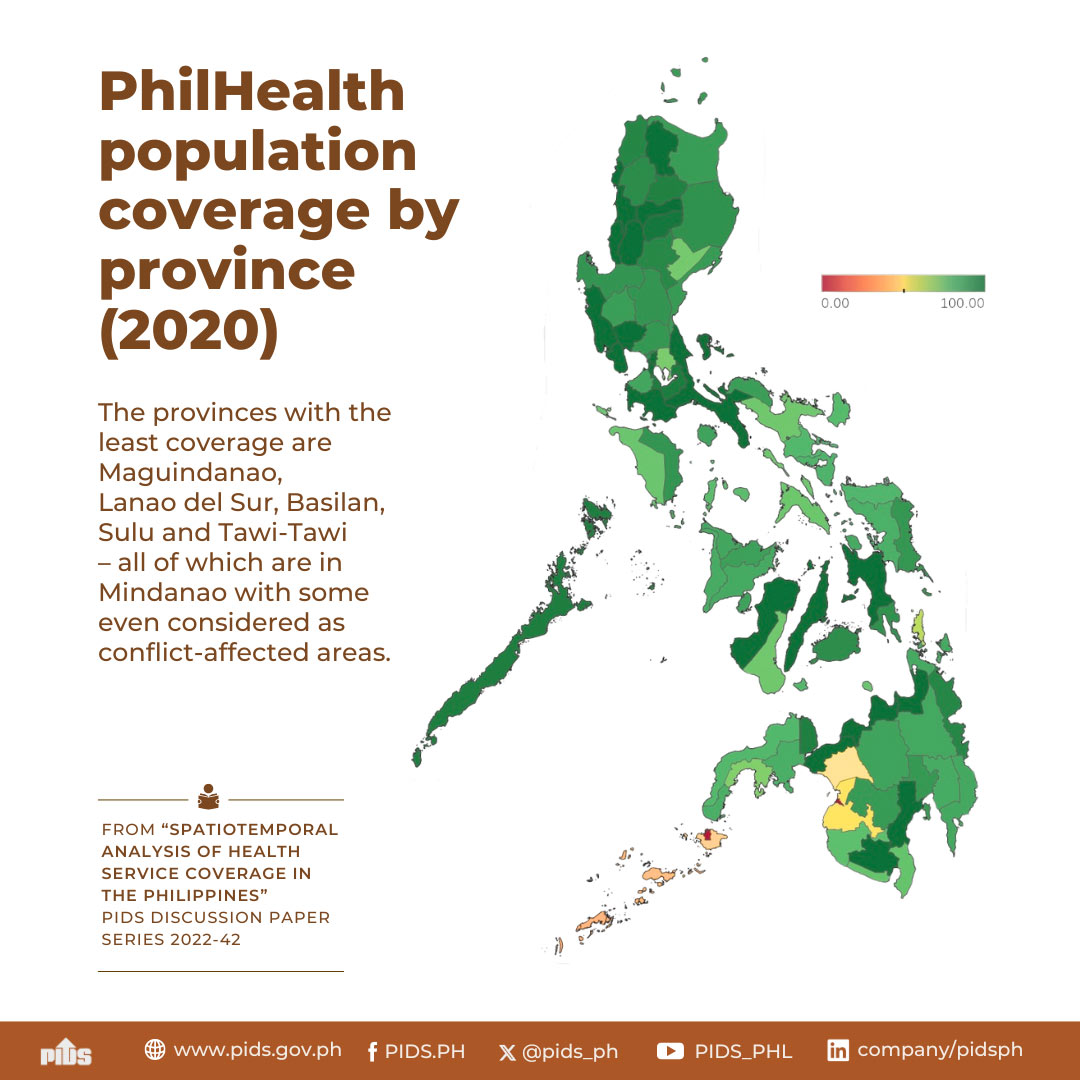

A second point to recognize is that small farmers and fishers are also consumers. They might suffer a decline in the price of goods they produce, but they will ultimately benefit because of the general decline in prices of agricultural and food commodities. This was shown in a study by Dr. Roehlano Briones of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, where agricultural trade liberalization was found to have led to higher welfare gains.

But do our politicians care whether malnutrition and stunting among our kids are the highest in Asean? Do they care whether half of our kids might suffer from brain malformation because of malnutrition? Do they care about the future of the youth and this country?

Sadly, a friend shared that our politicians don't for the very simple reason that they have a short-term perspective. My friend impishly remarked that once politicians win an election, they immediately think of two things: how to recover the huge expenses incurred in campaigning and how to generate enough resources for a reelection bid.

Having implemented good projects for the community during their term while in the pursuit of those financial objectives is unfortunately the best that we can hope for, my friend wryly concluded.