Married Filipino women are three to four times more likely than men to cite housework as their reason for not seeking employment, according to a study.

Held on 27 March by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) through its Socioeconomic Research Portal for the Philippines, the knowledge-sharing forum spotlighted the invisible but mounting toll of domestic labor—especially on women.

PIDS Senior Research Fellow Dr. Connie Bayudan-Dacuycuy warned that unpaid caregiving continues to limit women’s career opportunities, based on her analysis of Philippine labor patterns.

“The patterns that we observed five years ago still hold in the current setting,” Bayudan-Dacuycuy revealed, demonstrating how entrenched gender roles resist progress despite changing social norms.

Citing labor force surveys, Bayudan-Dacuycuy revealed that the trend is most stark among married female spouses and remains consistent across income groups.

“Women typically outperform men in terms of [housework] hours,” she noted, emphasizing that this imbalance persists across all economic classes.

According to Bayudan-Dacuycuy, the consequences of this imbalance extend far beyond individual households.

She presented startling international comparisons: South Korea with 0.8 and Japan with 1.3 fertility rates, which are considered “very low compared to the replacement rates” of these countries.

Bayudan-Dacuycuy drew a clear line between this trend and the unpaid labor expectations placed on women.

“More than half of the women preferred fewer children because they associate another child with more housework,” she said.

The Philippines’ 1.9 fertility rate—already below replacement level—suggests the nation is following its neighbors’ trajectory toward demographic crisis, she noted.

Furthermore, economic penalties compound these demographic challenges.

Bayudan-Dacuycuy’s data shows married Filipino women suffer a “motherhood penalty," earning P30 less daily than single women, while men enjoy a “wage premium” of P45 more when married.

“Firms may view the profession of training to these women as a risky investment,” she explained, describing how caregiving responsibilities limit women’s career advancement.

Root causes and the road ahead

The presentation identified three primary drivers of the imbalance.

First, economic specialization pressures.

“The spouse that commands the higher market price will, of course, go to the marketplace, and those that are not going to fetch a higher price will perhaps cut back and then do the housework,” Bayudan-Dacuycuy explained.

Second, biological assumptions position women for “light work” and men for “heavy lifting."

Third, patriarchal social constructs preserve “the dominance of men over women," particularly in traditional societies.

Bayudan-Dacuycuy proposed concrete policy solutions to address these interconnected crises.

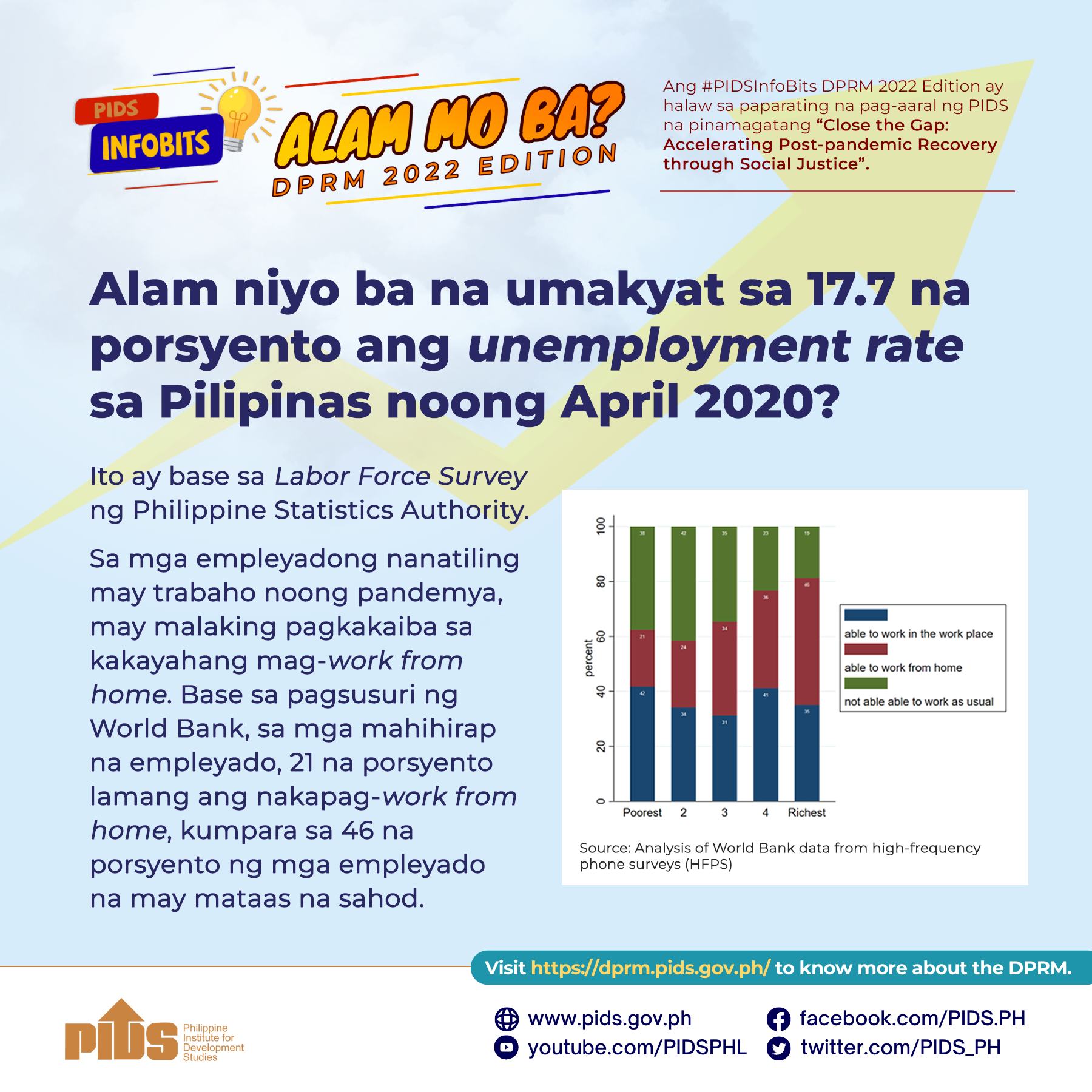

For workforce participation, she advocated “enhanced work-from-home opportunities” through programs like Strengthening the Philippine Workforce Through Adaptive and Responsive Digital Knowledge or SPARK, which provides digital skills training.

She emphasized improving public services with “longer contact hours in childcare services” and more reliable mass transportation to reduce time burdens.

Importantly, she cautioned against oversimplified fixes, such as paying wages for housework—a 1970s proposal that failed to gain traction.

“There is a lack of consensus on how exactly [you are] going to provide wage... It is not a long-term empowerment,” she said.

Instead, Bayudan-Dacuycuy called for comprehensive approaches that “empower women, both men and women actually, and help them to perform both their market and non-market work.”

Looking ahead

Demographic realities add urgency to these reforms. With the Philippines projected to become an aging society by 2045, she warned of coming elder care shortages.

“The increase in caregiving demands can lead to lower labor productivity—like, for example, absenteeism, tardiness,” Bayudan-Dacuycuy explained, suggesting the exploration of culturally sensitive solutions like “community-based elderly home” models to address this looming crisis.

Her final message was clear: recognizing and redistributing unpaid care work is no longer just a matter of fairness—it is an economic imperative.