The national government (NG) has spent nearly a trillion pesos on social protection programs between 2009 and 2017, but the seemingly hefty amount remained below international standards, according to a study released by the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

In a study titled “A Public Expenditure Review of Social Protection Programs in the Philippines,” PIDS Senior Research Fellow Charlotte Justine Diokno-Sicat and Senior Research Specialist Maria Alma P. Mariano said social protection expenditures in the country amounted to P948.434 billion between 2009 and 2017.

The authors said the government spent the most in social protection in 2017 at P179.011 billion. This was 34.9 percent higher than the P132.7 billion in 2016 and a 243.3-percent growth from the P52.144 billion posted in 2009.

“The Philippines spends lower on social assistance as a share of GDP [gross domestic product], 0.7 percent, than the average of 1.5 percent by lower middle-income countries,” the authors said. They, however, added that “there is still much to be done to increase the coverage for the Philippines to ensure that the poorest are adequately covered.”

The authors said social welfare programs received the largest portion of social protection expenditures with an average of 73 percent of total national government social protection expenditures for the period of 2009 to 2017.

On average, the social welfare sector, through the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), received 61 percent of total NG social protection expenditures. The government spent P83.181 billion annually on the average.

The government spent the most on social welfare programs at P748.627 billion between 2009 and 2017. These programs include the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program, which received the highest allocation at P388.237 billion.

The authors said social welfare involves preventive and developmental interventions that seek to support the minimum basic requirements of the poor and reduce risks associated with unemployment, resettlement, marginalization, illness and disability, old age and loss of family care.

Social welfare programs are usually direct assistance in the form of cash or in-kind transfers to the poorest and marginalized groups, as well as social services, including family and community support, alternative care and referral services.

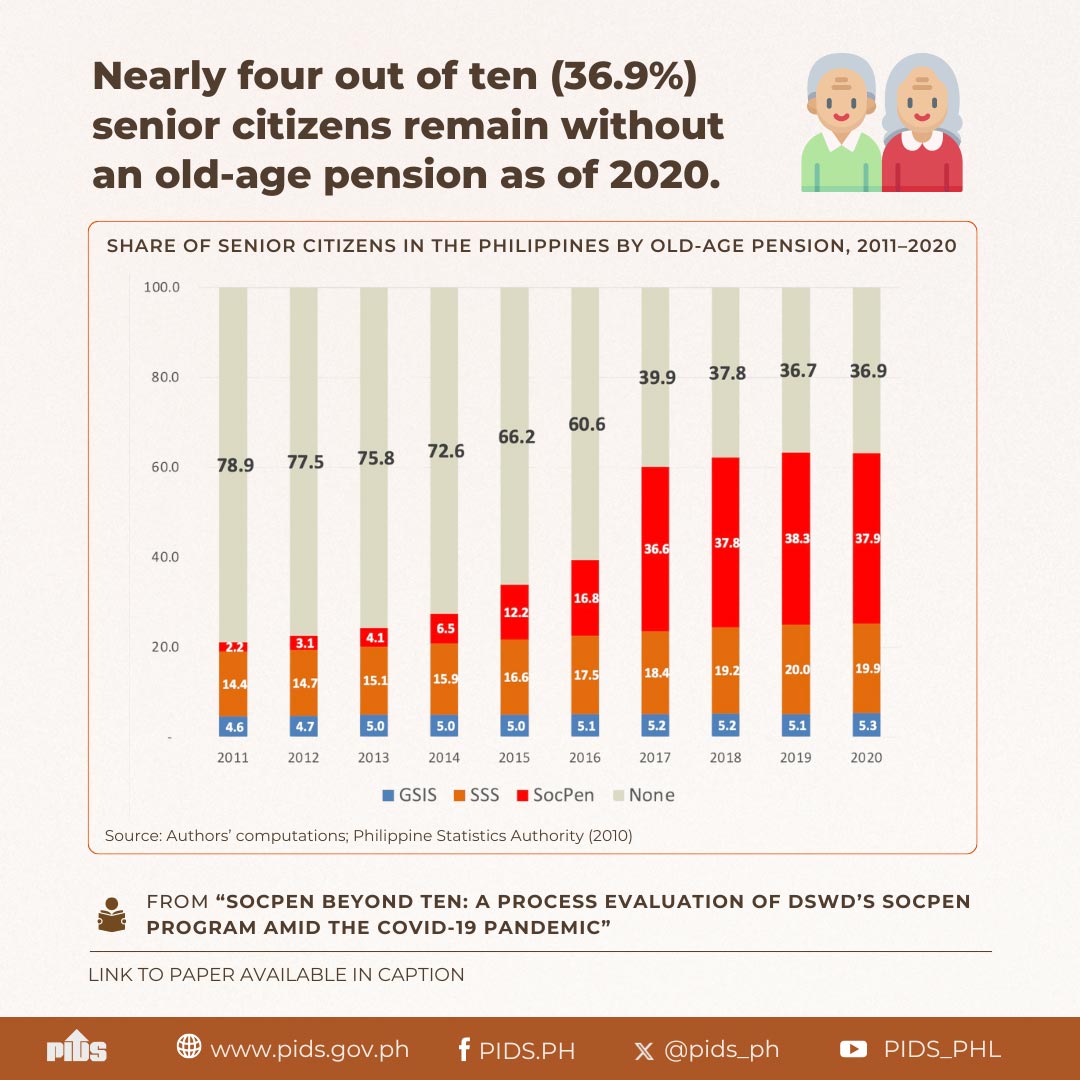

“The spikes in 2012 to 2015 can be attributed to the 86-percent increase in the Pantawid Program and about 80-percent increase in the Social Pension program of the DSWD,” the authors said.

The government spent the least on labor market interventions worth P4.849 billion. The government spent on average P539 million annually for these programs.

These include only two programs, the Special Employment Program for Students of the Department of Labor and Employment worth P3.71 billion and the Education Assistance Program of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples worth P1.15 billion.

Examples of interventions are skills development training, labor and trade policies and agricultural support. The goal, the authors said, is to address the risks of underemployment, unemployment and loss of income in the country.

“Labor market interventions contribute the smallest to social protection expenditures. One of the possible reasons is that these programs focus primarily on providing the means for Filipinos to finish schooling,” the authors said.

Earlier, Asian Development Bank (ADB) Principal Social Development Specialist Sri Wening Handayani said that if Asian countries fail to adopt innovative employment and social protection measures, many citizens won’t be able to afford retirement.

In an Asian Development Blog, Handayani said social protection can improve the future of Asian workers particularly the case in today’s gig economy where workers have short-term contracts, or are working as freelancers without any benefits such as retirement packages.

Currently, Handayani said the coverage of social protection programs in Asia is already very low compared to European countries.

Based on ADB’s Social Protection Indicator, less than half of Asia’s population was fully covered by at least one social protection scheme in 2015.

Handayani said the range varies from Japan with more than 90 percent to Nepal with less than 30- percent coverage.